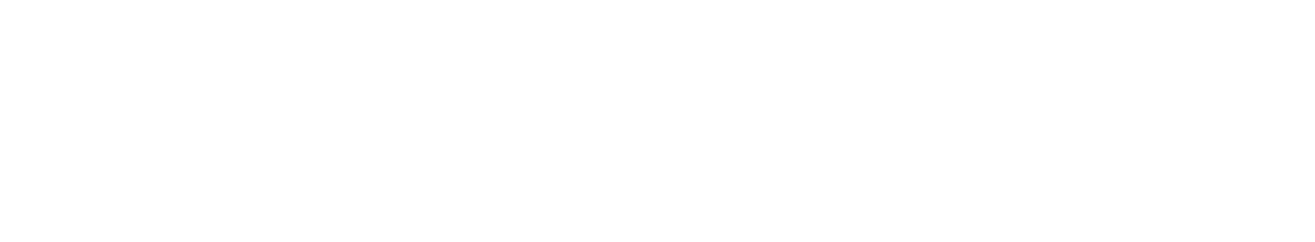

Among African drum traditions, the jembe of the Malinke and other Mande peoples has become an unprecedentedly global phenomenon. Mandinka kutiro drumming is closely related to the jembe tradition but comparatively little known outside of Gambia and Senegal. The kutiro ensemble consists of three drums: the accompanying kutirindingo (“small kutiro”), the almost identical but larger kutiroba (“big kutiro”), and the long, cannon-shaped sabaro, which is clearly related to, and likely borrowed from, the neighbouring Wolof sabar ensemble (some maintain that the kutirindingo and kutiroba originate with the Firdu Fula [notes to the Village Pulse CD Amadu Bamba: Drums of the Firdu Fula, VPU-1004]). All of the drums are played with a pencil-sized stick (in the strong hand) and a bare (weak) hand, which allows for a wide range of stroke qualities that can create the illusion of more than three drums playing. Some repertoire and styles use two bare hands for the kutiroba part; special pitch bending effects are created by pressing the centre of the drum skin with the elbow (weak hand) on the kutirindingo and kutiroba. The sabaro drummer also commands a police whistle that may be played in a rhythmic fashion, delineating short motives and longer phrases, or simply blown in natural tandem with his breathing, adding an edgy, frenetic craziness to the mix. (Most Westerners find the whistle to be an acquired taste but after initial impressions one grows to appreciate and indeed enjoy its biting intensity as an integral layer of the ensemble sound.) Like the jembe tradition, the typical venues for kutiro drumming are celebrations (especially weddings), recreational dancing, and agricultural work, although this latter function is comparatively rare these days. A kutiro event includes drumming, dancing and singing, which weaves a standard repertoire of short, strophic call-and-response songs with improvised social commentary based on melodic formulae.

Among African drum traditions, the jembe of the Malinke and other Mande peoples has become an unprecedentedly global phenomenon. Mandinka kutiro drumming is closely related to the jembe tradition but comparatively little known outside of Gambia and Senegal. The kutiro ensemble consists of three drums: the accompanying kutirindingo (“small kutiro”), the almost identical but larger kutiroba (“big kutiro”), and the long, cannon-shaped sabaro, which is clearly related to, and likely borrowed from, the neighbouring Wolof sabar ensemble (some maintain that the kutirindingo and kutiroba originate with the Firdu Fula [notes to the Village Pulse CD Amadu Bamba: Drums of the Firdu Fula, VPU-1004]). All of the drums are played with a pencil-sized stick (in the strong hand) and a bare (weak) hand, which allows for a wide range of stroke qualities that can create the illusion of more than three drums playing. Some repertoire and styles use two bare hands for the kutiroba part; special pitch bending effects are created by pressing the centre of the drum skin with the elbow (weak hand) on the kutirindingo and kutiroba. The sabaro drummer also commands a police whistle that may be played in a rhythmic fashion, delineating short motives and longer phrases, or simply blown in natural tandem with his breathing, adding an edgy, frenetic craziness to the mix. (Most Westerners find the whistle to be an acquired taste but after initial impressions one grows to appreciate and indeed enjoy its biting intensity as an integral layer of the ensemble sound.) Like the jembe tradition, the typical venues for kutiro drumming are celebrations (especially weddings), recreational dancing, and agricultural work, although this latter function is comparatively rare these days. A kutiro event includes drumming, dancing and singing, which weaves a standard repertoire of short, strophic call-and-response songs with improvised social commentary based on melodic formulae.

The present recording consists of performances recorded in the western Gambia in 1987 and 2002 by the same group of drummers led by Fina Korta. Based in Bakoteh, Fina Korta’s ensemble has been active in the Serrekunda area for over two decades. When I first met the group in 1987 Fina was a dynamic singer and dancer. He is now semi-retired and only performs rarely at “programs” (as their paid engagements are called) when the spirit moves him; he is present at all performances and manages the groups business affairs. Fina learned his art from Bakary Marong, who was active in the early 1970’s. While previous recordings of kutiro drumming have released short excerpts from longer performances (which is desirable for introducing this music to new listeners), this recording includes a longer excerpt that illustrates the flexible, telepathic shifting of rhythms that characterizes the performance practice and style of Fina’s group.

The present recording consists of performances recorded in the western Gambia in 1987 and 2002 by the same group of drummers led by Fina Korta. Based in Bakoteh, Fina Korta’s ensemble has been active in the Serrekunda area for over two decades. When I first met the group in 1987 Fina was a dynamic singer and dancer. He is now semi-retired and only performs rarely at “programs” (as their paid engagements are called) when the spirit moves him; he is present at all performances and manages the groups business affairs. Fina learned his art from Bakary Marong, who was active in the early 1970’s. While previous recordings of kutiro drumming have released short excerpts from longer performances (which is desirable for introducing this music to new listeners), this recording includes a longer excerpt that illustrates the flexible, telepathic shifting of rhythms that characterizes the performance practice and style of Fina’s group.

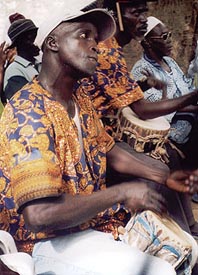

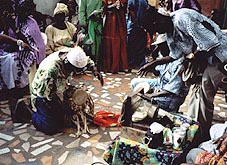

Fina leads a group that consists of a core of about five drummers, a singer (besides himself), which is supplemented by a floating or part-time contingent of another five or so drummers. A complete kutiro ensemble involves only three drummers: the lead sabaro drummer and two support parts (kutirindingo and kutiroba). Very infrequently, an occasion may arise when two sabaros play at the same time. In Fina’s ensemble, as few as four or as many as seven or eight players may show up for a gig/program. In the latter case, junior drummers get things warmed up before tagging off with the senior members halfway (or more) through the performance. The group functions as a collective small business wherein proceeds from a program are distributed between core members, who may not necessarily have even performed at the particular event. The ensemble collects proceeds from those attending the event in a gradual fashion throughout the program; rather than a lump payment, remuneration is a dynamic and ritualized form of busking, ebbing and flowing with the overall energy of the event. While expedient, Western-style networks surely exist within the daily lives of the drummers, a sense of genuine community predominates: people in long-term, caring and cooperative relationships defined by mutual commonality and obligation. It is clearly evident that the musicians actually like being around each other, as they meet on a daily basis to hang out on the frequent days without work; some members regularly walk several miles in order to do so. Extensive sitting, with the accompanying sipping of tea, sharing of meals and conversation, is an integral component of the social life of drummers. Ensemble members usually assemble at a venue several hours before their performance in order to sit and relax; food and drink are then usually supplied by the host of the event.

Fina leads a group that consists of a core of about five drummers, a singer (besides himself), which is supplemented by a floating or part-time contingent of another five or so drummers. A complete kutiro ensemble involves only three drummers: the lead sabaro drummer and two support parts (kutirindingo and kutiroba). Very infrequently, an occasion may arise when two sabaros play at the same time. In Fina’s ensemble, as few as four or as many as seven or eight players may show up for a gig/program. In the latter case, junior drummers get things warmed up before tagging off with the senior members halfway (or more) through the performance. The group functions as a collective small business wherein proceeds from a program are distributed between core members, who may not necessarily have even performed at the particular event. The ensemble collects proceeds from those attending the event in a gradual fashion throughout the program; rather than a lump payment, remuneration is a dynamic and ritualized form of busking, ebbing and flowing with the overall energy of the event. While expedient, Western-style networks surely exist within the daily lives of the drummers, a sense of genuine community predominates: people in long-term, caring and cooperative relationships defined by mutual commonality and obligation. It is clearly evident that the musicians actually like being around each other, as they meet on a daily basis to hang out on the frequent days without work; some members regularly walk several miles in order to do so. Extensive sitting, with the accompanying sipping of tea, sharing of meals and conversation, is an integral component of the social life of drummers. Ensemble members usually assemble at a venue several hours before their performance in order to sit and relax; food and drink are then usually supplied by the host of the event.

Gambia has undergone immense social change in the past two decades, the most striking of which is the dramatic increase in Western tourism. Serving as a sun destination for British, Dutch, German and Scandinavian tourists is a mixed blessing. While drawing in much needed foreign currency and capital, most of this remains in the hands of foreigners and wealthy Gambians, with only a small trickle-down effect reaching the impoverished locals. The burgeoning business of sex tourism (largely targeting Gambian gigolos) has created difficult social tensions within the mainstream Muslim society. While the extensive tourist infrastructure built along the Atlantic coast has opened up new performing opportunities for local musicians, they must cater to an international, highly transient audience (most people come on a one week holiday package) unaware of local culture and indeed laden with inaccurate stereotypes regarding “African music.” The jembe has made its presence felt here in both craft stalls and drum circles on the beach; the repertoire played by the jembe drummers I encountered seemed like an ersatz practice that bore little relation to Malinke or adapted Senegambian traditions. All of the musicians that I knew from the mid 1980s said that they were worse off now; indeed, the number of traditional performance events in private Gambian homes for both jalis and drummers was noticeably reduced in 2002. Despite the erosion of venues and practices, kutiro drumming is still relatively easy to encounter and thankfully remains a vital part of Gambian life.

Gambia has undergone immense social change in the past two decades, the most striking of which is the dramatic increase in Western tourism. Serving as a sun destination for British, Dutch, German and Scandinavian tourists is a mixed blessing. While drawing in much needed foreign currency and capital, most of this remains in the hands of foreigners and wealthy Gambians, with only a small trickle-down effect reaching the impoverished locals. The burgeoning business of sex tourism (largely targeting Gambian gigolos) has created difficult social tensions within the mainstream Muslim society. While the extensive tourist infrastructure built along the Atlantic coast has opened up new performing opportunities for local musicians, they must cater to an international, highly transient audience (most people come on a one week holiday package) unaware of local culture and indeed laden with inaccurate stereotypes regarding “African music.” The jembe has made its presence felt here in both craft stalls and drum circles on the beach; the repertoire played by the jembe drummers I encountered seemed like an ersatz practice that bore little relation to Malinke or adapted Senegambian traditions. All of the musicians that I knew from the mid 1980s said that they were worse off now; indeed, the number of traditional performance events in private Gambian homes for both jalis and drummers was noticeably reduced in 2002. Despite the erosion of venues and practices, kutiro drumming is still relatively easy to encounter and thankfully remains a vital part of Gambian life.

For Gambian drummers, music exists as an integral part of everyday life and not subject to the artificial separation of the soundproofed studio that is often preferred in Western culture. Indeed, the idea of recording kutiro drumming is foreign to them, as Gambians are only interested in live performances—a sure and encouraging sign of the continuing vitality of the tradition. When recording, the musicians were generally not concerned about the background or ambient noise (as defined by most Westerners) of daily living such as birdsong, children playing, work being done, doors opening and closing, which is evident on some tracks.

Performers:

Kutirindingo: “Doudou,” Mankeba Sanne, Janko Sidibe

Kutiroba: Solo Diba, Dembo Jatta

Sabaro: Massaneh Damfa, Mankeba Sanne, Keba Sanne, Haruna Baldeh

Lead vocals: Fina Korta, Lamin Toure

Tracks

1. Fere (4:33). This is the end of a 20 minute performance done in an improvised “studio” context. The melody of this song was taken from an old recording of Fina’s mentor Bakary Marong from the early 1970s. The musicians often sang this tune, deliberately reintegrating it into the current music scene of the Serrekunda area, not unlike the proclivity of DJ’s for remixing “golden oldies.” When playing for themselves at home, the musicians would drum with rhythmic vitality but surprising dynamic restraint, approaching a chamber music aesthetic that is rarely encountered in West African percussion music.

2. Kutiro Program (26:56). The following tracks are taken from a continuous performance at a wedding celebration in Lamin, Gambia in 2002. The succession of spontaneously shifting rhythms here is typical of the group’s style of kutirodrumming. Tantan wulindo (0:00) or “beginning drumming” is traditionally the first piece in such programs, opening with a solo on the sabaro followed by a series of five related rhythmic patterns, each played for a short period. While the musicians identified five distinct rhythms in discussions, the number seemed to vary in actual performance.

Stylo (1:52) is the trademark Mandinka rhythm for accompanying songs. Generally known as Seruba when sung by a male singer of the drum ensemble, the musicians identify it as Stylo when sung by one of the (amateur) women attending the party. Fina recalls that the popularity of this audience participation number grew in the past ten years. Rhythmic density, elaboration and tempo increases—at which point the rhythm is known as Fere (6:32)—as the song gradually builds excitement and anticipation before spontaneously giving way to Lenjeng (10:06). Lenjeng is the dramatic climax of drum programs. It is general the sabaro drummer that assesses the needs of the crowd and decides when to shift gears to this vigorous dance but the transition can be more ambiguous and extended at times. While performances of Lenjeng available on commercial recordings feature a continuous rhythmic stream, Fina’s group performs in “stop time” style consisting of: a resting pattern to tread water while waiting for the next dancer to enter the dancing circle; a variety of driving, full-tilt patterns that accompany the dancing; and a cadential signal that ends dancing and drumming with a full stop. This cycle is repeated as needed throughout dancing phases of a program (ie., when not resting during the Stylo/Seruba singing sections). There is frequently a dovetailing of the high-energy portions of the cycle due to the quick entry of another dancer. In this tradition the drummers follow the dancers, who take turns entering the dance circle; this often occurs when a dancer’s energy appears to be flagging, at which point she is joined by or politely (but firmly) pushed aside by the next participant (the Lenjeng dance is an intense cardio experience that cannot be sustained for more than 45 seconds or so). Musaba julo (15:30) is a less athletic dance rhythm named after and designed for the participation of “older” women in the crowd. A skeletal version of the rhythm (similar to Seruba but with a triple subdivision of the beat) is used to accompany songs, which are initiated and sung by women attending the event. The name of the rhythm implies, but does not result in, age segregation at dance events: any women fit enough to dance Lenjeng may do so, regardless of age and, likewise, younger women may dance to Musaba julo is they so wish. In this performance the density and flow of the rhythm increases (19:43) until it slides into a suitable groove for dancing (21:19).Musaba julo occasionally accompanies a collective gathering and simultaneous shaking of buttocks by a large group of women, who point their pulsating posteriors in the direction of the drummers

3. Seruba-Fere/Lenjeng (13:18). After an hour and a half and several rounds of the Stylo-Fere/Lenjeng cycle, the event gathers momentum and the microphone is passed on to Lamin Toure, who now functions as the main singer of Fina’s ensemble. This track begins about 8 minutes into the song and gathers increasing rhythmic drive as it shifts to Fere (4:40), continuing to intensify until the group breaks into their standard set of transition rhythms (9:20) leading to Lenjeng. The actual shift to Lenjeng hangs in suspension (10:00) until finally emerging clearly (around 10:40), illustrating the dynamic, organic way in which rhythms both support and reflect the social interaction of an event. Recorded in Banjul, 2002.

4. Birds (0:53). Gambia is an important site for bird watching, as many species make a stopover during migrations to and from Europe. This short excerpt exemplifies the rich polyphony of a morning chorus (actually a late chorus, around 7:30 am) typical of the summer soundscape. One can briefly hear at the beginning of the track (at around 15 seconds) a bird known locally as the Pra, whose call brings to mind the groove of Lenjeng. While the drummers were amused with this observation, they attached no explicit significance to it. (The performance of the rhythm Kassa on Mamady Keita’s CD Wassolon: Percussions malinke [fmd 159] also features a birdsong that resembles the Pra).

5. Presidential polyrhythm (1:18). The preceding avian soundscape is juxtaposed here with a short excerpt recorded in Banjul in 2002. The opening of a new bakery was celebrated by a five groups of drummers from various ethnic communities of The Gambia—two Wolof sabar ensembles, a Jola dance group including the bugarabu drums, and two Mandinka kutiro groups—along with a DJ blasting pop music from the PA system. While waiting for President Jammeh to arrive and officially open the bakery, ALL of these ensembles played simultaneously in a joyful noise of intense rhythmic energy (and madness!). The microphone was located close to Fina’s group, so that their contribution of Musaba julo is fairly recognizable in the collage. Rainer Polak has described a similar performance practice in Mali whereby ensembles superimpose various rhythms at random and then, at a climactic moment, converge in sync with the same rhythm (liner notes to the CD Donkilo: Call to dance [Pan 2060CD]). I recall a wedding reception in 1987 where two jalis, separated by a distance of three or four meters, played entirely different songs at the same time while individual members of the audience tuned in (and out, I suppose) whichever musician they chose. Similarly, I witnessed two kora players conduct a lesson and play “in unison” with instruments that were tuned to entirely different pitch levels.

6. Lenjeng (6:53). This track was recorded (using analog tape) in July 1987. It begins with the introductory rhythm “kundin-din-dinkun-(ba-da-),” which was frequently used during that time to warm up the crowd at the beginning of a session (while waiting for dancers to enter the dance circle). The excerpt moves through several cycles of the “wait-dance-stop” form. As with many West African drum traditions, the kutiro drums can be used to express a discreet semantic content to those familiar with such language. The unison elbow bends of the accompanying drums (at 5:21) refer to a Fula man in the community. Drum language is also used for such pragmatic requests as soliciting drinking water or lighting a cigarette. The kutirindingo player “Doudou,” was a virtuoso performer of decorative, pitch-bending “elbow work,” amply evident on this track.

7. Seruba (3:02). While kutiro drumming is characterized by frenetic energy, the quiet, pensive quality of this track shows another attractive but little known side of the tradition. This is the beginning of the same performance from track 1 (based on a revived tune by Bakary Marong); the group is “counted in” by Fina.